It seemed, at one point, that the dust had settled. The digital age was in full swing and there was a clear sense of “before” and “after.” Millennials were the first generation to strictly occupy the “after.” As “digital natives,” they would usher in a world where digital was the norm, not the exeption. But as Gen Z comes of age and forms their own generational identity, the definition of “normal” has shifted once again.

Social media, while not quite as groundbreaking as the whole of digital technology, has nonetheless become a part of daily conversations about everything from international politics (election meddling) to interpersonal relationships (#MeToo). As “social natives,” Gen Z is reminding everyone that the digital revolution is now a digital evolution.

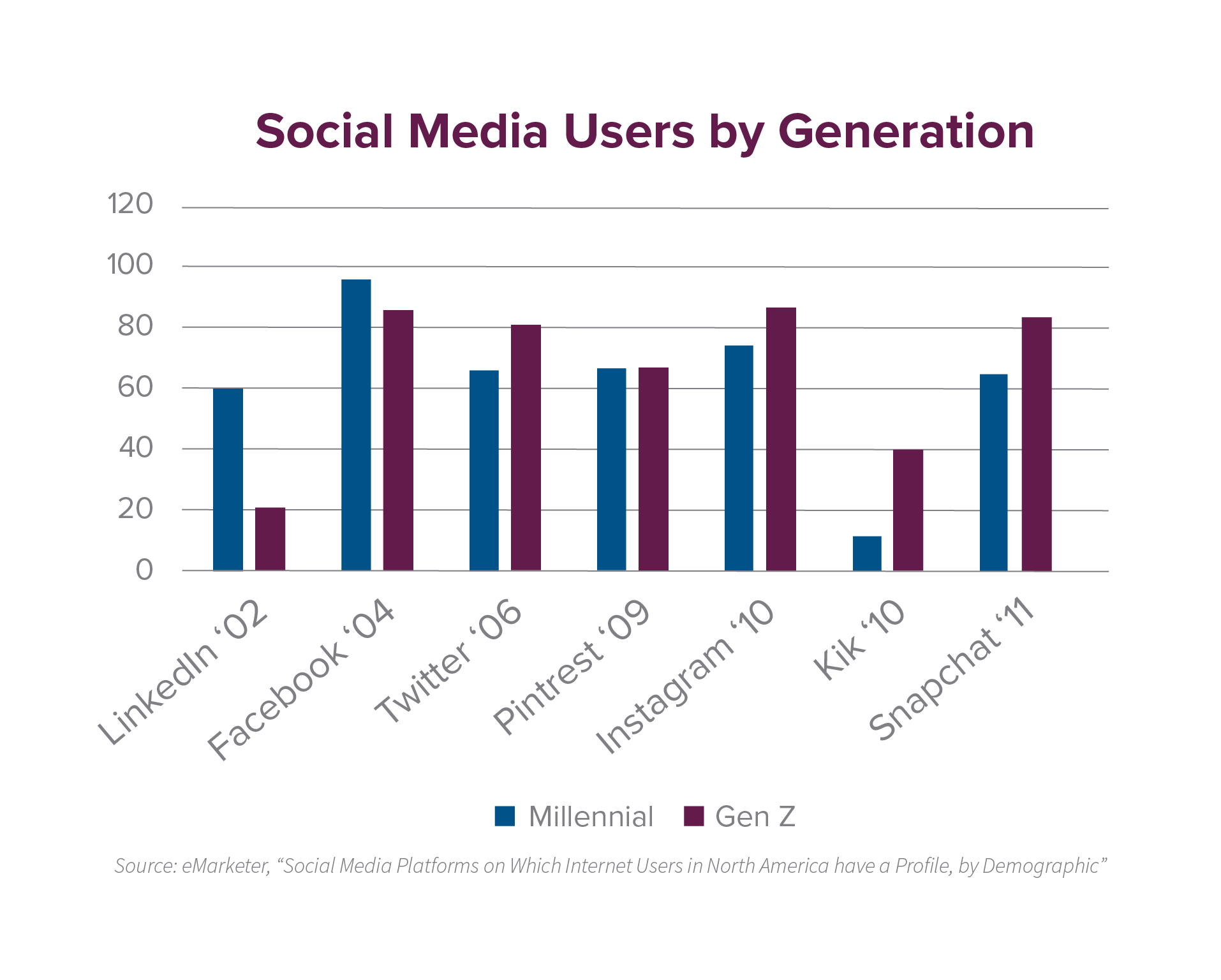

Millennials are old enough to remember the dawn of social media: MySpace in 2003 (and Friendster before that), followed by Facebook in 2004. With YouTube launching in 2005 and Twitter in 2006, much of the current social media landscape was well established by the time even the oldest members of Gen Z hit double digits. And though the oldest ranks of Gen Zers certainly remember Instagram hitting phones in 2010 and Snapchat’s appearance in 2011,

Read MoreIt seemed, at one point, that the dust had settled. The digital age was in full swing and there was a clear sense of “before” and “after.” Millennials were the first generation to strictly occupy the “after.” As “digital natives,” they would usher in a world where digital was the norm, not the exeption. But as Gen Z comes of age and forms their own generational identity, the definition of “normal” has shifted once again.

Social media, while not quite as groundbreaking as the whole of digital technology, has nonetheless become a part of daily conversations about everything from international politics (election meddling) to interpersonal relationships (#MeToo). As “social natives,” Gen Z is reminding everyone that the digital revolution is now a digital evolution.

Millennials are old enough to remember the dawn of social media: MySpace in 2003 (and Friendster before that), followed by Facebook in 2004. With YouTube launching in 2005 and Twitter in 2006, much of the current social media landscape was well established by the time even the oldest members of Gen Z hit double digits. And though the oldest ranks of Gen Zers certainly remember Instagram hitting phones in 2010 and Snapchat’s appearance in 2011, they would still have been young teenagers, likely experiencing these introductions before their familiarization with geometry, the periodic table, and the Bill of Rights. This adoption of social media at a significantly earlier life stage (the timing that makes Gen Zers “social natives”), seems to explain not only many of the differences in the ways millennials and Gen Zers use social media, but also some of the underlying attitudes defining these population groups at scale.

APPETITE FOR DISRUPTION

Perhaps the most definitive dichotomy between natives and non-natives of any kind is integration versus disruption. In terms of technology, this would refer to non-natives having to learn and adjust as developments arise. Natives are integrated to existing technologies from the start; if someone can’t remember being taught how to use a toaster, they are a toaster native.

Overall ubiquity (the integrated advantage of natives) allows Gen Z to quickly adopt to new platforms and use more platforms for more activities in what has always been a connected life. On the other hand, millennials often report being overwhelmed in the digital world they created.

Much has been made of digital and social media’s negative consequences. Self-monitoring applications have been created to stop us from constantly checking our phones, and recent studies by the Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology have found that Facebook can cause anxiety and depression. Given that Nielsen depicts Gen Z as using by far the largest and most diverse selection of various digital and social media, it might seem that our societal ills have just begun. However, KSM’s research, based on MRI data, found that Gen Zers were much more likely than millennials to cite the internet as a positive influence, showing high indices for statements like “something that relaxes them” (+26 percentage points), “a good escape” (+9), and “puts them in a good mood” (+24). So why the disconnect?

It could be that these youths are simply less jaded; indices across both generations are very positive, and don’t seem to reveal the aforementioned crises of the digital age. But this data also showed that Gen Z respondents went so far as to agree that, more often than not, technology has little impact on their daily lives. They also agreed with this same statement much more often than millennials when “internet” was swapped for “technology.”

For brands, the implication is the challenge of matching these levels of integration. A promoted tweet or post is a highly-recommended social tactic at KSM. As our extensive research and experience in retail has shown, promoted tweets can increase offline sales by up to 29 percent, and this is likely driven by millennials, Twitter’s core user. Gen Z however, might respond better to a native message from an influencer. Influencers are the social media celebrities who Gen Zers obsess over following as they do everything from sport the latest fashion to play videogames to remove new products from their boxes.

The latter strategy in some ways shucks the media concept of heavy-ups and key periods which are perfect for a promoted tweet. For sustained brand influence, KSM would always recommend an extended relationship if pursuing influencer marketing. At work here is the idea of impact social messaging (millennials) versus seamless consistency (Gen Z).

PUT UP A PARKING LOT

Millennials’ trek into a culture surrounded by social media has been anything but seamless. For instance, why do 35 percent of universities and 70 percent of employers look at social media accounts before making acceptance or hiring decisions? Because most people reveal themselves there. Take the iconic case of Justine Sacco, a communications executive who sent an inappropriate and offensive tweet to her personal account in 2014. This tweet made her a lightning rod for internet shaming before she was fired and publicly disgraced. Modern history is filled with these examples, and the outcome is rarely pretty. Gen Z has subsequently learned from these kinds of mistakes. Using the world’s largest social media service as an example, Statista data reveals that Gen Z posts far less to Facebook than their elders or, in an increasing amount of cases, they just go elsewhere. Facebook will continue to grow this year, and who knows for how many years into the future. That said, its under-24 audience is projected to shrink by about 2 million, while Snapchat, Kix, and other platforms have become the parking lot behind the high school gym; no grown-ups (almost a quarter of Facebook users are 55 or older) and no supervision (universities and employers certainly aren’t scanning Snaps).

One would hope this trend has more to do with a premium on social media privacy than a network of loopholes for seedy material. But the ultimate point is that Gen Z is going to make social media their own space, often in more unique ways than millennials have. Take “finstas,” the second Instagram account available to a users’ select-group, which many Gen Zers operate in addition to their main account.

One would hope this trend has more to do with a premium on social media privacy than a network of loopholes for seedy material. But the ultimate point is that Gen Z is going to make social media their own space, often in more unique ways than millennials have. Take “finstas,” the second Instagram account available to a users’ select-group, which many Gen Zers operate in addition to their main account.

These “secret” accounts are used for more personal, revealing posts and have strict security settings, while their public accounts feature highly-curated, sanitized content safe for parents and employers alike. Instagram, like many social media giants, often ends up following their users upon discovering trends like this. In this case, however, brands have the opportunity to be leaders. For example, Canadian fashion brand Ryu’s #WhatsInYourBag campaign invited users, on any of their accounts, to simply post their own images of the Ryu swag they love for a chance to win more. Putting spend behind the user-generated concept with promoted stories (at top of Instagram app, not in-feed), Ryu nailed this opt-in and, most importantly, non-invasive social activation which generated thousands of posts. While not completely out of the box, it was a campaign that made sure the brand was not crashing the parking lot uninvited, something which is extremely tempting to any marketer looking at the scale and engagement numbers behind social media.

Millennials may pick up a few of these Gen Z privacy hacks or simply self-correct to avoid embarrassing snafus, but they will not likely cease to be a generation that is comfortable providing information in exchange for content. An overwhelming preference for social login, a Facebook-dominant practice where users log in to various systems by granting access to social data, is evidence of this. However, brands should be sure to take advantage of the data pool before Gen Z’s privacy prudence and shunning of Facebook, as well as events like the data breaches of that very same platform, shore up or complicate access.

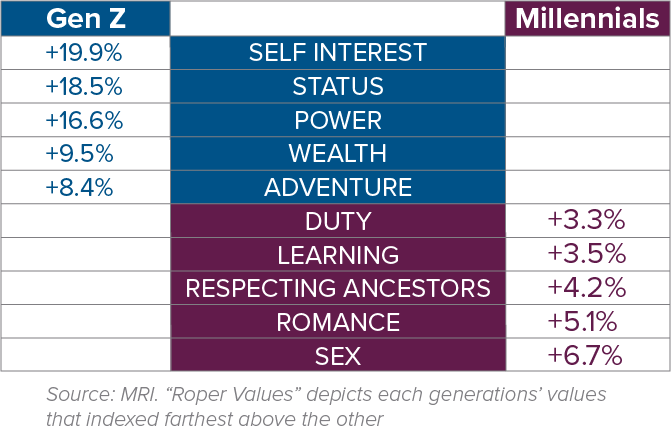

As the economy and level of opportunity has begun to pick up steam for Gen Z, one could assume from this data that the result has been rampant narcissism. But there is plenty of evidence that this strong sense of self will lead Gen Z in a positive direction. Because they believe one person can make a difference, this generation will participate in more volunteering and activism. The most relevant marketing phenomenon resulting from this proclivity towards self is the influencer.

It is KSM’s outlook that influencers’ popularity amongst Gen Zers is derived from their relatability. They do normal things and just happen to be especially apt at using social media, or perhaps have gotten lucky with a personal following that somehow went viral. For Gen Z, 63 percent prefer this type of figure to a celebrity because it could be them. Of the generation’s top 10 favorite celebrities, only one of them, Jennifer Lawrence, was of the “traditional” making. Millennials, on the other hand, still appreciate the “J-Laws” of the world. A recent omnichannel campaign from Tourism Australia, which culminated in a Super Bowl ad, pushed all the right buttons—celebrity-studded and packed full of late-80’s references—and got that generation talking across the social spectrum. It was successful precisely because this buzz was generated by a community and was outward-facing (towards the celebs and campaign humor). For Gen Z, something like the #Realstagram campaign has proven more appealing. Led by an influencer, it gave Instagram users the opportunity to reject unrealistic beauty standards, while at the same time providing an opportunity to get in front of the lens.

THE LAST WORD: MOVING AHEAD AND MANAGE EXPECTATIONS

The social native is young yet completely familiar with a space that is still hazy to most around them. Gen Z is more savvy, more assertive of their standards, and has claimed more ownership over processes in the social media landscape. Brands preparing for this up-and-coming market will have to not only match their understanding, but also obey it. This does not mean marketing to millennials, still the market to win in advertising today, is different: the rules are just less stringent. Instead, millennials have established a different set of expectations (brand-led interaction, information exchange, shared value) which, though they may be refined by Gen Z, have still in no way been mastered by marketers and require just as much continued attention.