First, a bit of history:

Over the past few years Google has rolled out a number of changes they claim are improving the search experience, while at the same time making the marketplace more competitive. One of the largest updates was the removal of the right-hand rail in February 2016. That update significantly reduced available ad inventory, and forced advertisers to put a big emphasis on achieving one of the top three average positions. Failing to do so often resulted in a large drop off in impressions, clicks, and sales. Occupying a lower position on the search engine results page can be very efficient, but also limit reach. This change has also had a bigger impact on mobile where ad space is extremely limited.

So why did they make the change? One assumption is Google determined it could generate more revenue for this premium inventory, because of the higher costs required to achieve top-three placement. Many accounts were impacted and costs rose—most noticeably in non-branded cost-per-click campaigns, while branded campaigns were impacted but not as much.

Other recent paid search updates from Google have been heavily focused on driving automation. Google pushes that goal by allowing their algorithms to make decisions on how to improve performance. There is value in this automation, but it needs to be balanced out by human intervention. Without careful oversight, many of the bidding strategies fall short and miss the nuances of an account. For example, when leveraging position-based strategies within branded campaigns the algorithm has been shown to make some poor choices. In one scenario that was targeting top position, the bidding algorithm continued increasing cost-per-click bids to consistently achieve top placement. This approach significantly increased cost while netting a very minimal gain in sales, which ended up hurting overall performance and cost per acquisition. Even more concerning than these sorts of inefficiencies, a higher use of this automation diminishes transparency and makes it easier for Google to gain more control over this revenue source.

Without careful oversight, many of the bidding strategies fall short and miss the nuances of an account.

So let’s talk about Google’s latest update:

The latest shift is that Google is now removing “average position”—a core paid search metric. Average position shows the average placement of a brand’s ad relative to others during a specified period of a campaign. It was one of the few metrics that stood out since the early days of paid search.

Because it’s a significant change, Google is giving advertisers a fairly long timeframe to adapt: The removal of average position is not expected until September 2019. In the meantime, Google has released four new metrics to essentially replace average position, which are available now:

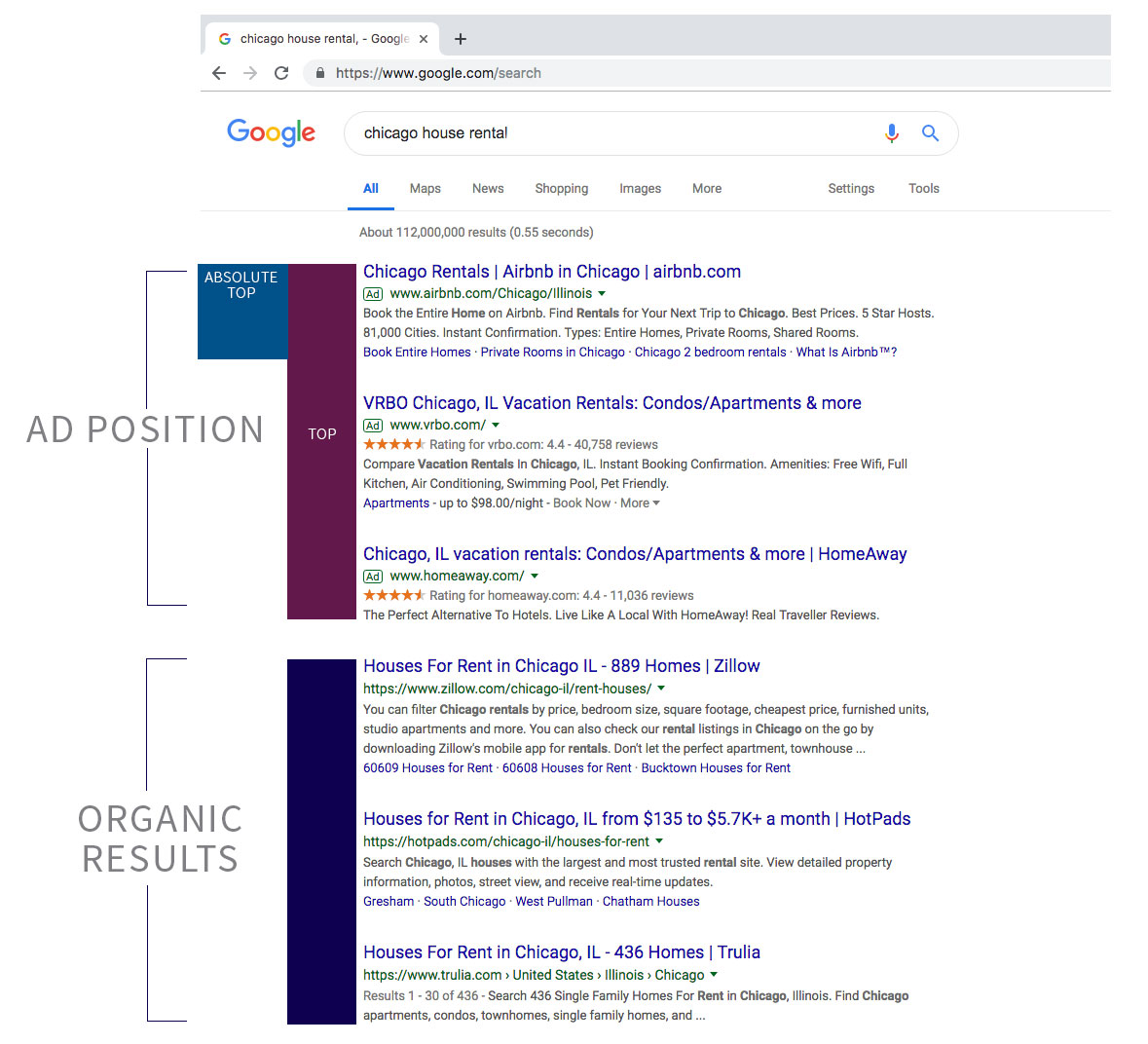

- Absolute Top Impression Rate: This is the percent of a campaign’s total ad impressions that are shown as the very first ad above the organic search results

- Top Impression Rate: This is the percent of impressions that are shown anywhere above the organic search results.

- Search Absolute Top Impression Share: This is the percentage of your search ad impressions that are shown in the most prominent search position (Absolute Top Impression Share = absolute top impressions / total eligible top impressions).

- Search Top Impression Share: Percentage of your search ad impressions that are shown above organic search results (Top Impression Share = top impressions / total eligible top impressions

While there are definitely good aspects to these new metrics, the fact remains that adjustments will need to be made since many advertisers and bidding platforms relied on average position as one of the key data points when making decisions. In the past, savvy advertisers had picked up tricks to optimize around this metric. It was well understood that click-through-rates rose and more ad extensions would show as an ad moved up the page. And if bids were set too low or the market was noncompetitive, Google would move ads below organic listings or reduce the number of auctions you were eligible for, choosing to show more organic listings instead. This limited scale because cost didn’t meet Google’s threshold, so advertisers would bid up to overcome this fault and thus capture additional volume. The good news is that now under the latest changes, similar optimizations will actually be clearer to execute with Google giving advertisers more data around ad prominence.

Rather than focusing on one metric to explain how ads are showing, agencies will need to contextualize the balance between these four new metrics.

What do these changes mean for advertisers?

Google is saying that average position doesn’t carry the same weight it used to and is re-adjusting, which is fair. That’s because paid search no longer has up to 10 or more ads all serving on the first page. Today’s search is now more focused on achieving top positions, which is why the new metrics emphasize the measurement of ad prominence. Going forward it will be key for advertisers to understand and get used to these metrics as they provide more information than average position alone could. Nearly everyone (platforms included) is going back to the drawing board to rethink their bidding strategies. Helping brands understand the implications of these changes will also prove tricky for some, since rather than focusing on one metric to explain how ads are showing, agencies will need to contextualize the balance between these four new metrics.

Although this is a big update, savvy marketers will adapt and find the benefits. KSM has long taken the stance that being in the top three ad spaces is key for success, since it often achieves the reach necessary to drive strong performance. Top Impression Rate will now take over as the primary metric used to measure success in this new format. For many brands, the focus will be on maximizing this number relative to budget and performance. In the early days of this update we expect cost-per-click to swing as everyone is learning, but eventually settle at similar “pre-switch” levels. And for those seeking a similar metric to average position under this new model, there is a formula for determining a close equivalence via a weighted average that’s calculated with total impressions, absolute top rate, and top impression rate (assuming there are two or three slots above organic results). Within branded campaigns, the absolute top impression rate will be the key focus.

No matter what, brands can certainly expect more analysis on the nuances of these metrics as we approach September. While some may lament the loss of average position, savvy marketers are celebrating access to more metrics that will help guide their campaign decisions.